Place-based education is celebrated for its ability to be student-centered and meaningful. It allows teachers to naturally integrate multiple subject areas, creating rich, interdisciplinary learning experiences. This approach also aligns with Indigenous ways of knowing, which emphasize the importance of learning from the land and understanding the relationships between people, place, and nature. Indigenous cultures often teach through stories and hands-on experiences, fostering a sense of connection to the land and a responsibility to care for it. By embracing place-based education, teachers can honor these perspectives and help students develop a deeper understanding of their role within their environment and community.

As a geographer, I was taught to view most land and landscapes as hybrid landscapes, shaped and modified by human interaction. This includes the parks we visit or even the streets we walk down. Since humans are part of nature, place-based learning doesn’t need to be limited to only pristine, untouched environments. In my teaching practice, I broaden the definition of place-based learning to include learning from both the land and the community. It’s about making real-world connections and exploring the places where we live, work, and play.

By widening the concept to examine places through time and space, students can gain a deeper understanding of why a location is the way it is today. This also allows them to explore issues facing their communities, whether it’s solid waste management or invasive species, and develop authentic solutions. In this way, place-based learning becomes synonymous with community learning or local-based learning.

Some key goals of place-based education include student engagement through active, hands-on learning, inquiry-based learning where students ask meaningful questions that guide their discovery, and critical thinking as students not only ask questions but also observe thoughtfully, make connections, and answer complex questions; even in elementary school, children often have more capacity for deep thinking than we give them credit for.

Middle School Example: Sustainability at Vancouver’s Olympic Village

The Olympic Village neighborhood in Vancouver is often cited as a model for sustainable urban design. From water drainage and recycling systems to renewable energy use, the area is packed with green innovations like green roofs, energy-efficient buildings, and extensive bike lanes. I took my middle school students to Olympic Village for a day-long field trip to explore these features firsthand.

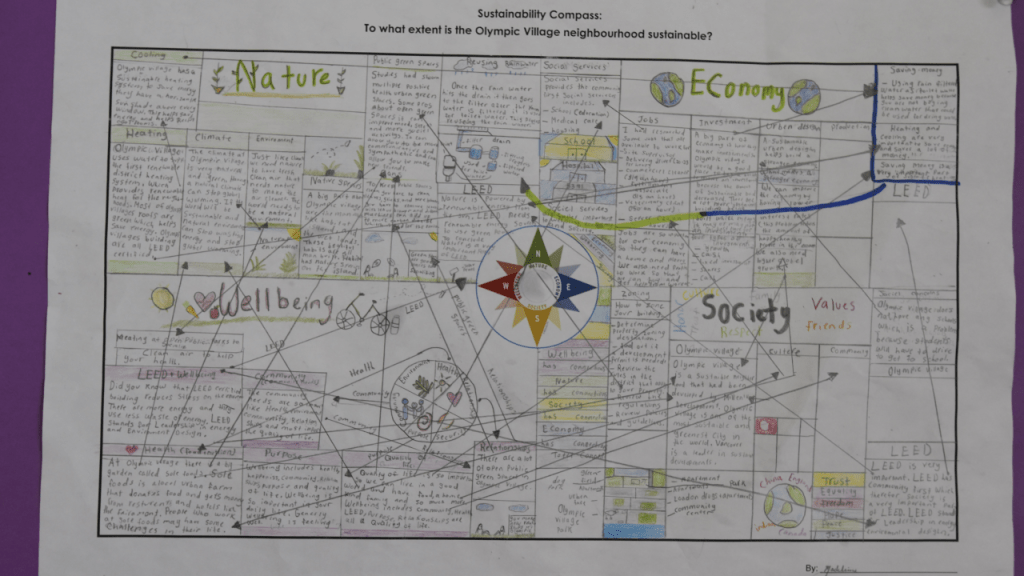

In preparation, we researched the neighborhood and discussed the types of sustainability features we might encounter. Students were also introduced to the sustainability compass, a tool that helps analyze sustainability through four lenses: nature, economy, society, and well-being.

During the field trip, I guided them through the neighborhood, pointing out various features while encouraging students to make connections with their learning. Along the way, we met with local community leaders and agency workers who discussed their roles in the neighborhood. For instance, we spoke with a representative from Soul Foods, who shared how they employ at-risk individuals while helping to feed the community. Students also learned about social housing projects and energy initiatives in the area.

Throughout the day, students were tasked with observing sustainable features and noting what they felt was missing from the neighborhood. Some noticed that the absence of a local school was a drawback, as it meant families had to commute, potentially increasing carbon emissions and limiting children’s social connections within the community. Furthermore, although it was a dry day, students noticed there were no public spaces with covered areas which might impact residents’ willingness to go outside in the rain. Others pointed out that although the community center was LEED certified, it lacked a library, which forced residents to travel further. On the positive side, they appreciated how well connected the area was, with its bike lanes, public transportation, and abundance of public spaces.

One of the biggest takeaways from this experience was how students began to understand systems thinking. They saw how various elements of the neighborhood, its environment, infrastructure, and social services, were interconnected, and how these systems contributed to, or hindered, its overall sustainability.

Addressing Local Issues: The Downtown Eastside

In another example of place-based learning, older students can explore the Downtown Eastside of Vancouver to better understand the social and economic challenges facing the area. By studying the historical, cultural, and spatial factors that have shaped this neighborhood, students can begin to grasp the root causes of issues like homelessness and addiction.

A well-rounded exploration would include examining the area’s physical geography, such as its proximity to the port and water, as well as its historical evolution. This includes looking at how changing economic priorities and social policies have affected marginalized groups. After classroom discussions, students could visit the Downtown Eastside to observe the neighborhood and meet with organizations working to address these issues. This helps students connect abstract social justice topics to real-world situations, encouraging them to think critically about potential solutions.

Real-World Learning: Expanding Place-Based Education

Other place-based learning opportunities might include visits to a local landfill or recycling center, where students can explore the lifecycle of waste and the importance of sustainability. When discussing zero waste or the circular economy, students could visit businesses that practice what they preach, such as a zero waste grocery store or a business that reuses materials to make new products, like Chopvalue, which reuses chopsticks to make furniture and decor. They could also study a watershed, visiting the source such as Capilano or Seymour watersheds, following the journey of water from its source to where it ends up, learning about its various uses along the way.

One of the most important aspects of place-based education is intentionality. Teachers should have clear goals but remain flexible, allowing student inquiry to shape the learning process. I encourage teachers who might be considering how students might connect and learn from the community, including urban environments to build real-world community experiences. The aim is to help students connect their classroom learning to the world around them in meaningful, lasting ways.

Leave a comment